At long last I have scanned all 104 pages – plus covers – of my manual for the Singer 431G sewing machine and am thereby reminded why I’d been putting it off so long!

I hope it is useful to all who have requested it; enjoy!

(c) the blogger.

Vintage Sewing Machines, books, attachments and a few self-drafted projects thrown in too…

26 Sep 2019 10 Comments

in Manuals

At long last I have scanned all 104 pages – plus covers – of my manual for the Singer 431G sewing machine and am thereby reminded why I’d been putting it off so long!

I hope it is useful to all who have requested it; enjoy!

(c) the blogger.

22 Oct 2018 1 Comment

in Book Reviews

If you are familiar with sewing books of this vintage you could definitely be forgiven for wanting to skip the chapters that cover the construction and finishing techniques as you will doubtless be familiar with them already, in print if not also in practice but I would urge you to read it through regardless as like many other of the best-known authors in this field, Agnes Miall writes from long, personal experience and to skip sections is to potentially miss some useful, anecdotal nugget, doubtless won through personal error, which you may not find elsewhere.

Moving to the book’s ‘unique selling point’, it focusses on the figure faults of the more mature woman. I’m not certain that everyone (or indeed anyone) falls neatly into one of the main six figure types but that said, the advice given about style types is sensible and the guidance on fitting is good.

You won’t find any patterns here. It’s not that kind of book. It’s very much aimed at the home dressmaker who uses commercial patterns and it rightly pays a great deal of attention to the primary rule of commercial patterns which is to make the majority of alterations to the paper pattern itself, before EVER cutting it in fabric, so that alterations in the cloth will be minimized and no cloth will be wasted.

Be prepared to scream out loud when you hear what the threshold is for reaching “middle age”. Whisper it quietly and then discard this information forever. Thirty five.

Once you’ve picked yourself back up off the floor, comfort yourself with the thought that as this book was written at a time when fewer people carried extra weight before reaching that age, here in the 21stcentury it is certain that the modifications suggested here will be useful to as many below that age as above it, dealing largely as it does with accommodating extra flesh.

The six figure types are each given a name (Leonora, Penelope, Juno, Editha, Marianne and Augusta) and these names are frequently mentioned in the text, forming a neat reference to the types most likely to benefit from whichever modification is being described, e.g. “…Marianne and perhaps Editha, who are very generously built in front, may find too much room in the back…” and “”Skirts with a number of pieces or gores are more flattering to the older figure (especially to Augusta’s ample hips) than straight ones cut in only two pieces. So a golden rule for Mrs Over-Forty [yes, that threshold has shifted] to remember is that fitting will very likely need to be done on eachof the seams.”

Another useful reference point about this book is its use of numbered paragraphs for the three chapters which cover fitting. These are then listed in a ‘Fitting Ready Reckoner’ which is set out in a table of six columns, one for each type, under which is listed the numbers of the paragraphs most likely to be needed when fitting that particular type. She also suggests that the first time one uses the book, it is helpful to mark with a pencil tick each of the paragraphs found to be pertinent which is another useful hint I have not seen elsewhere.

The main chapter headings are:

I Getting Ready

II Older Figures and Styles that Suit Them

III Concerning Paper Patterns

IV Cutting Out and Marking

V Tacking Your Dress Together

VI Fitting – Shoulders and Neck

VII Fitting – Bust, Back, Hips and Waist

VIII Fitting – Armholes and Sleeves

IX Darts, Seams and Pressing

X All About Sleeves

XI The Neck of Your Dress

XII Binding and Rouleaux

XIII Plackets, Belts and Pockets

XIV The Hem and Finishing Touches

XV Blouses, Skirts and Underwear

XVI Altering Ready-Made Clothes to Fit

XVII Cutting Down and Remodelling Clothes

Index

Plates

Agnes Miall is very thorough and competent in her explanations. She explains things fully but remains focussed so it is easy to follow her guidance whilst losing track of the point she makes.

I’m not sure I’d recommend this book to anyone who has been making (and fitting) clothes since their early adulthood as even if the fitting issues begin to increase and appear in different places than formerly, most will nonetheless be familiar to those competent in recognising and addressing the source of such things. If someone is coming to dressmaking later though, or with a bit of excess weight already in place, then this will be helpful.

That said, it’s worth it for the read alone, and also for the polite euphemisms such as “sit-upon” for bottom.

Copyright of the blog owner 2018

02 Sep 2017 39 Comments

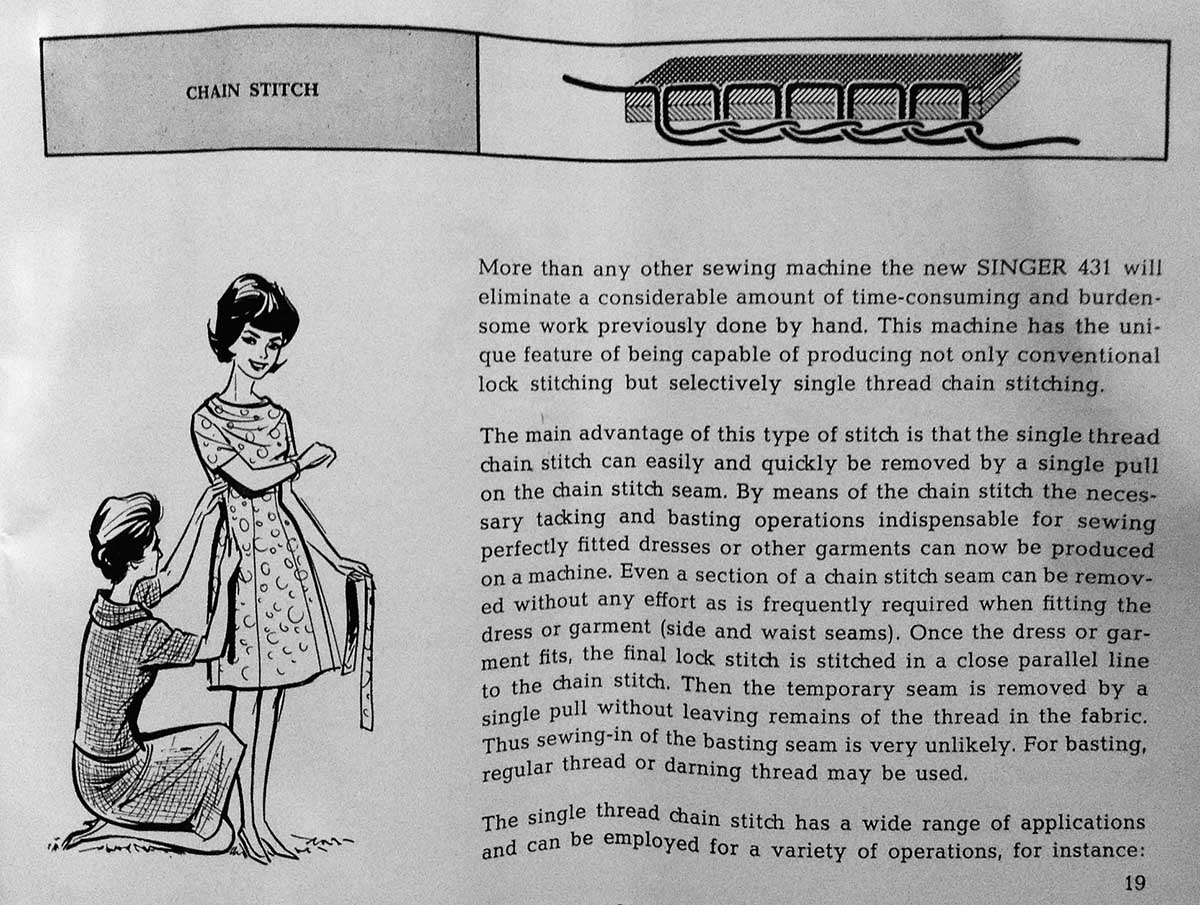

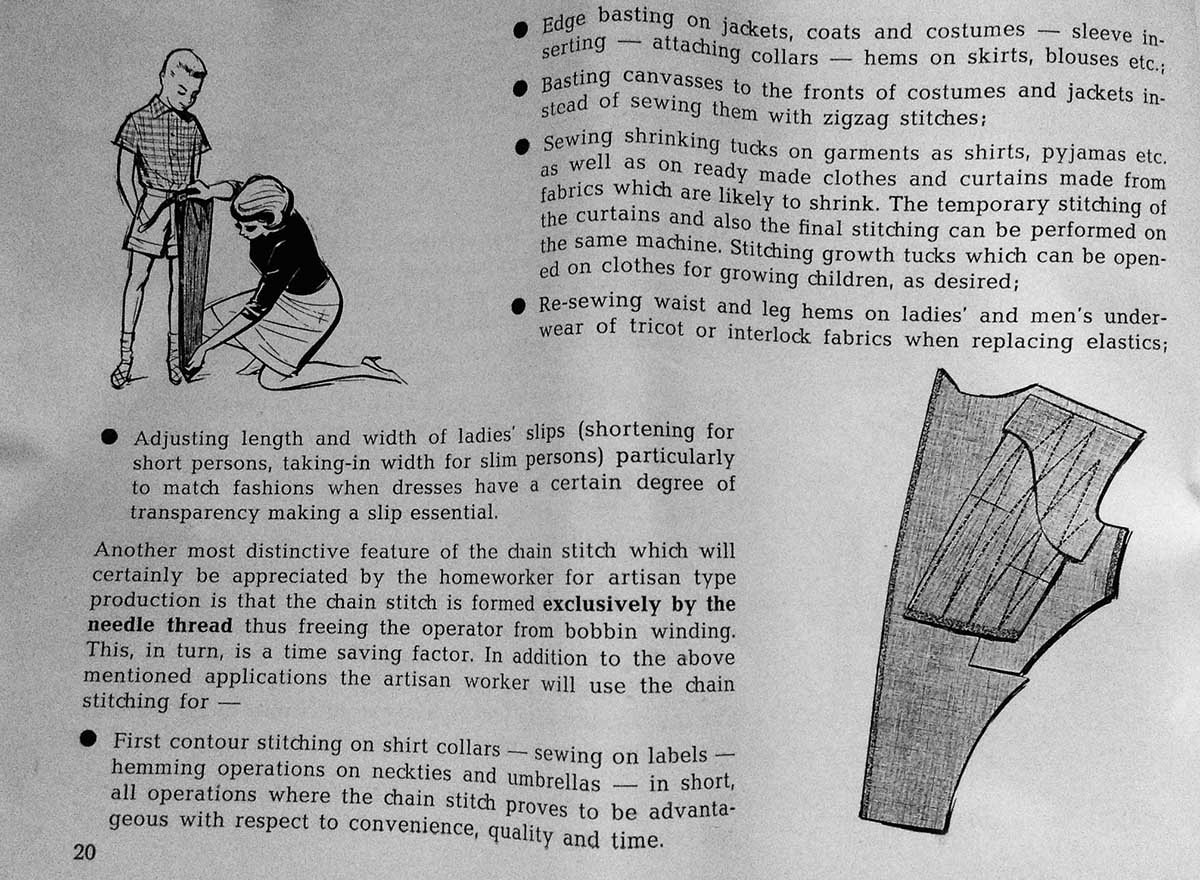

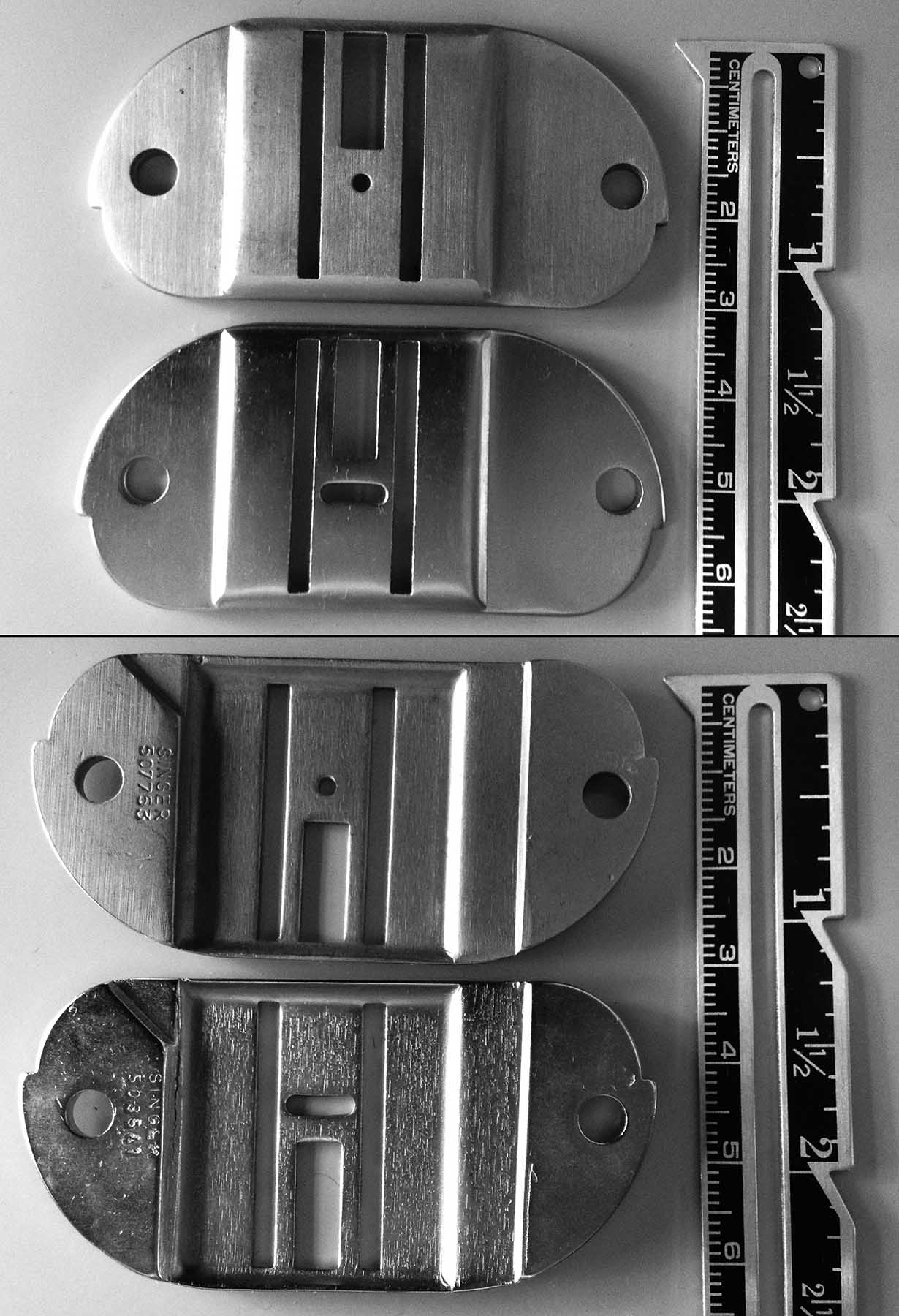

The Singer 431G has been on my wish list for quite a few years now. I patiently waited for one to come within reach and finally managed to secure one for a decent price and at a distance possible for me to collect it in person. I took a bit of a chance with it as I didn’t manage to find out what accessories and plates were included before hitting the “Buy” button but I was lucky. The only thing missing is the straight stitch plate but as I have many dedicated straight stitch machines, I don’t mind that. The general (zig zag) stitch plate will work just as well and I do of course have a LOT of options when it comes to sewing a straight stitch on fabrics that require the smaller needle hole. Of much more importance to me is that the chain stitch plate is present, which it is, together with the general plate and two cover plates and a full set of feet, cams and bobbins.

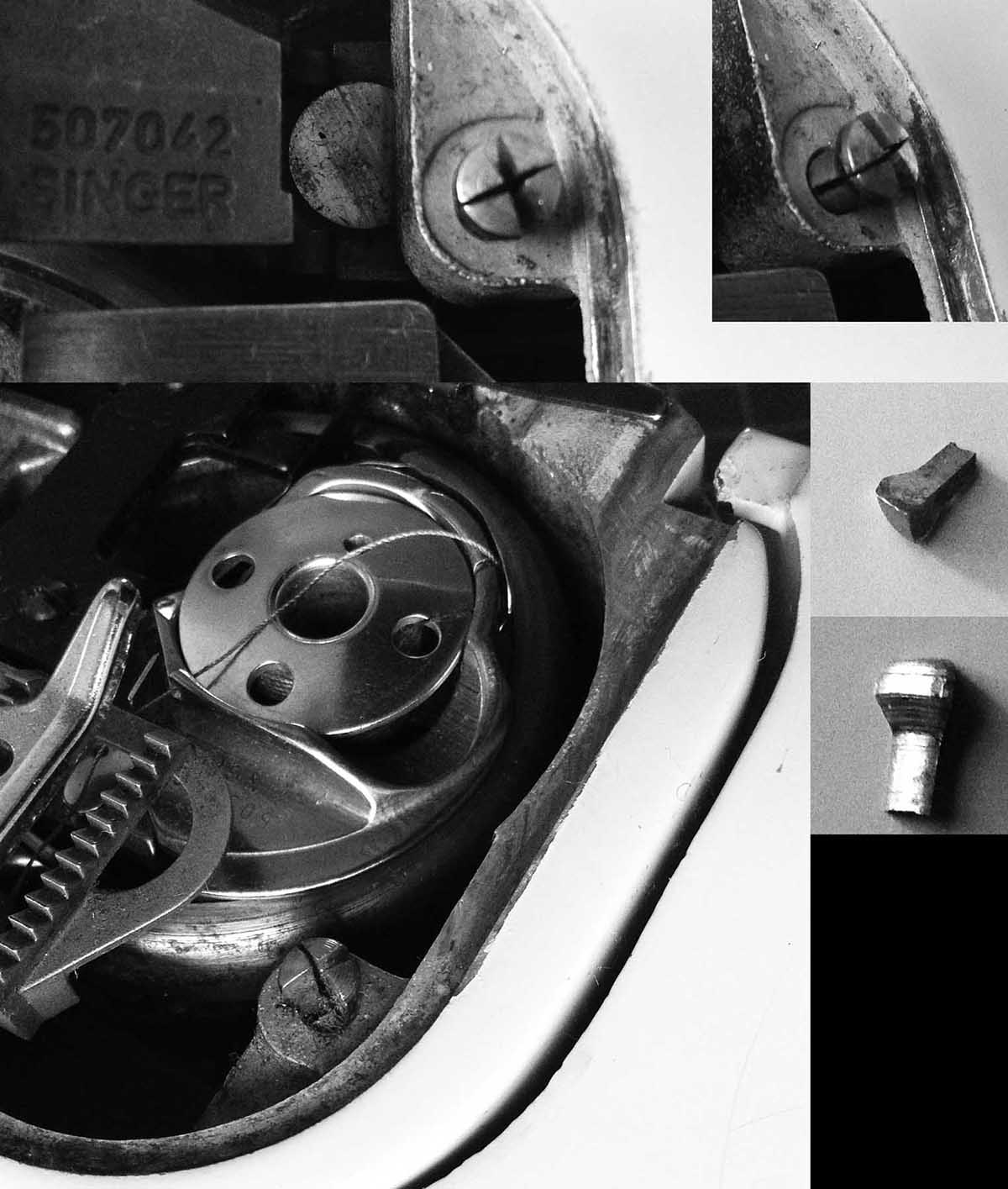

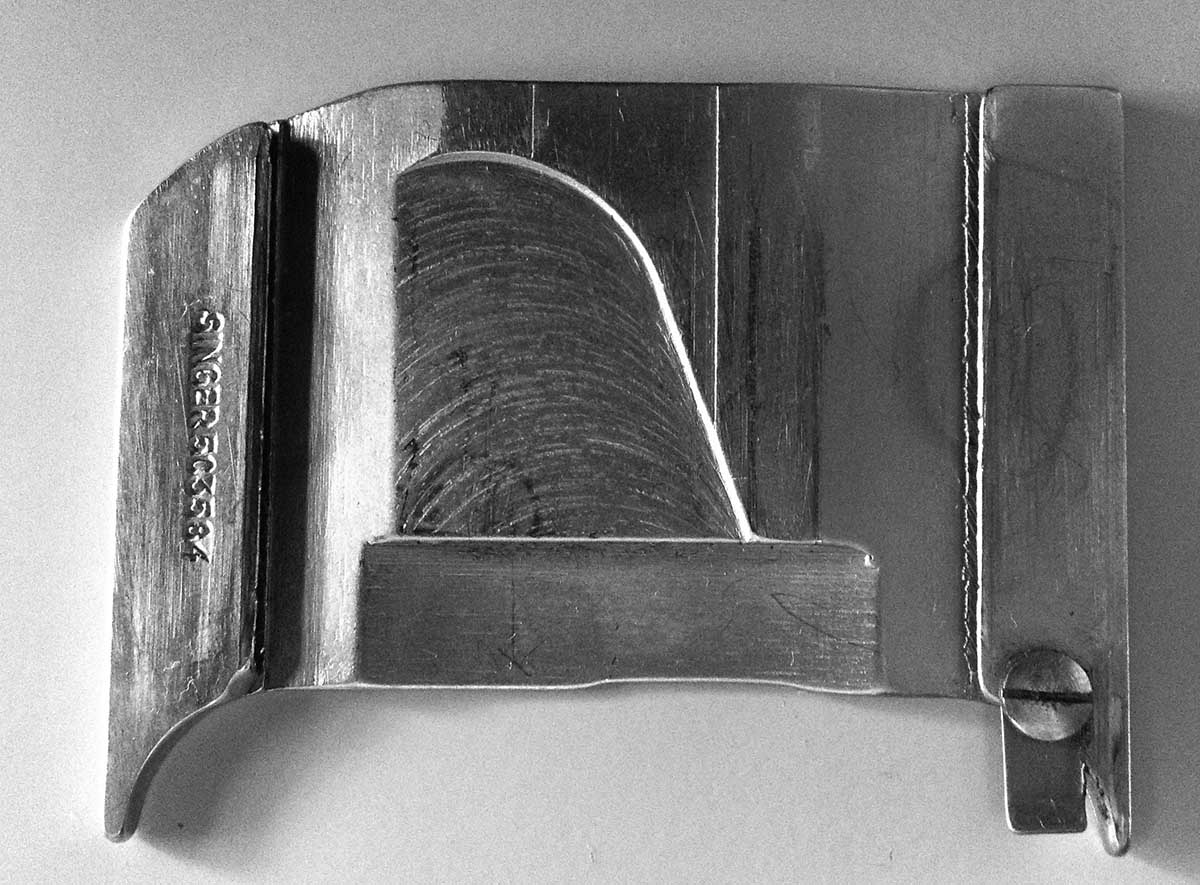

I always give new arrivals a thorough clean and service and removing the needle plate I discovered the ‘achilles heel’ of these machines: that is the fragility of the clamping pins over which the plates fit. These are a mushroom-domed pin, cut vertically down in quarters, which allows the pin to squeeze together a bit when the plate is passing over it. I managed to snap off one quarter when I was lifting the needle plate free.

The complete, unbroken one is shown above left and right. The broken on is shown at the bottom, together with two views of the broken piece to the right of the photo.

I doubt it can easily be fixed; it is too small to drill and pin and glue would not be sufficiently resilient to the constant strain of having plates squeezed over and prised off it repeatedly. I shall just have to be careful not to dislodge any more. It seems to hold absolutely fine with three quarters of the pin and a quick Google search shows me that this is a common problem. If sufficient sections come free as to make it unusable I shall simply drill out the stumps and tap in a straight pin of correct dimensions to fit the holes in the needle plate or else tap in a threaded insert and use some ordinary needle plate screws.

Researching this machine before bidding, I found very little. I’m not particularly surprised by this as what I did find out was that they had a very limited production run in the early 1960s. I can’t find a serial number on her at all…I’ll continue to look but I’ve searched all the usual places.

Those of you who are familiar with my machine reviews will know how much importance I place on facts and figures so here follows some definitive data about the serial numbers of the accessories and plates which came with my machine. I can’t guarantee that all of them are original but the plates all fit and so do the feet.

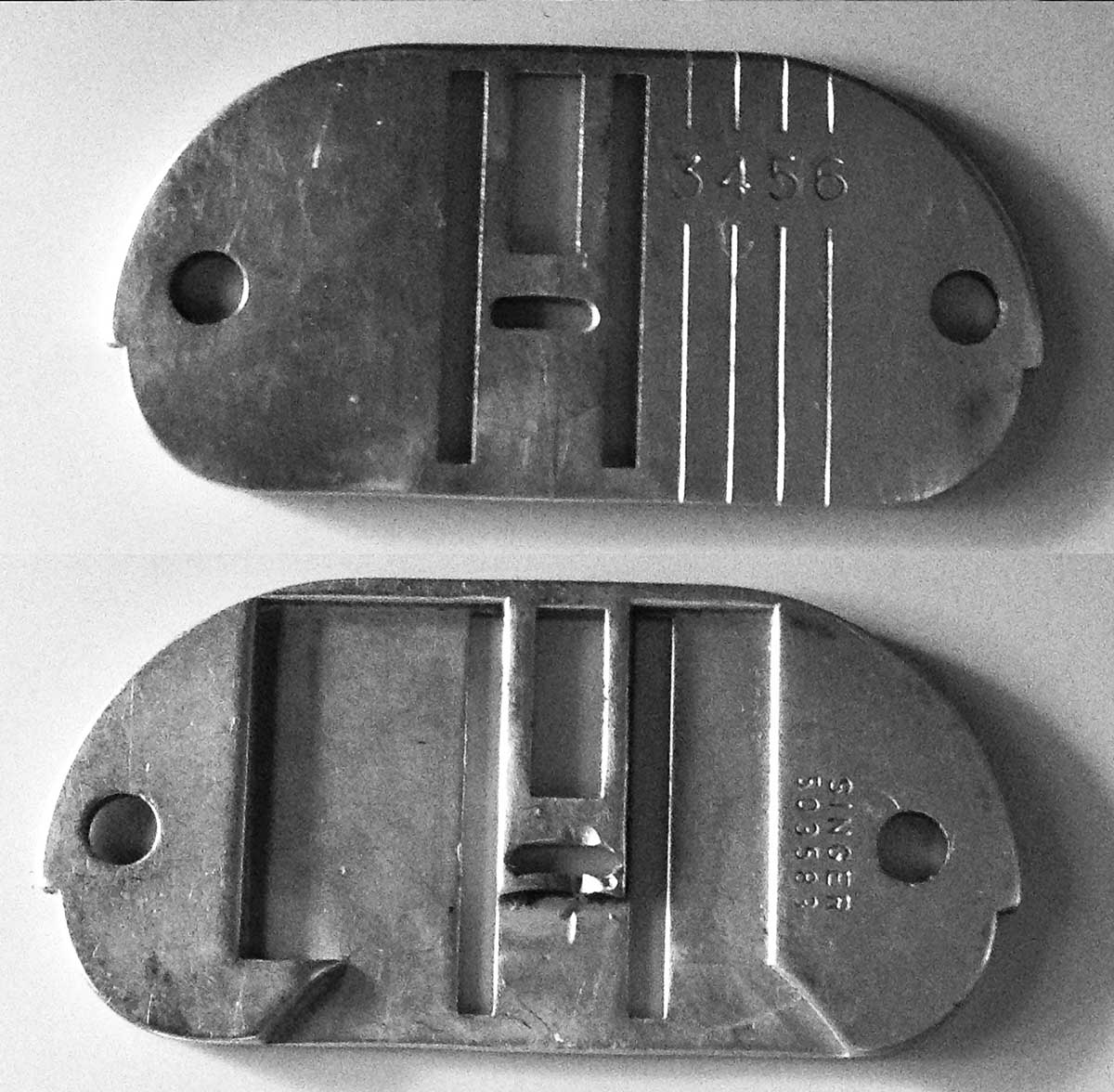

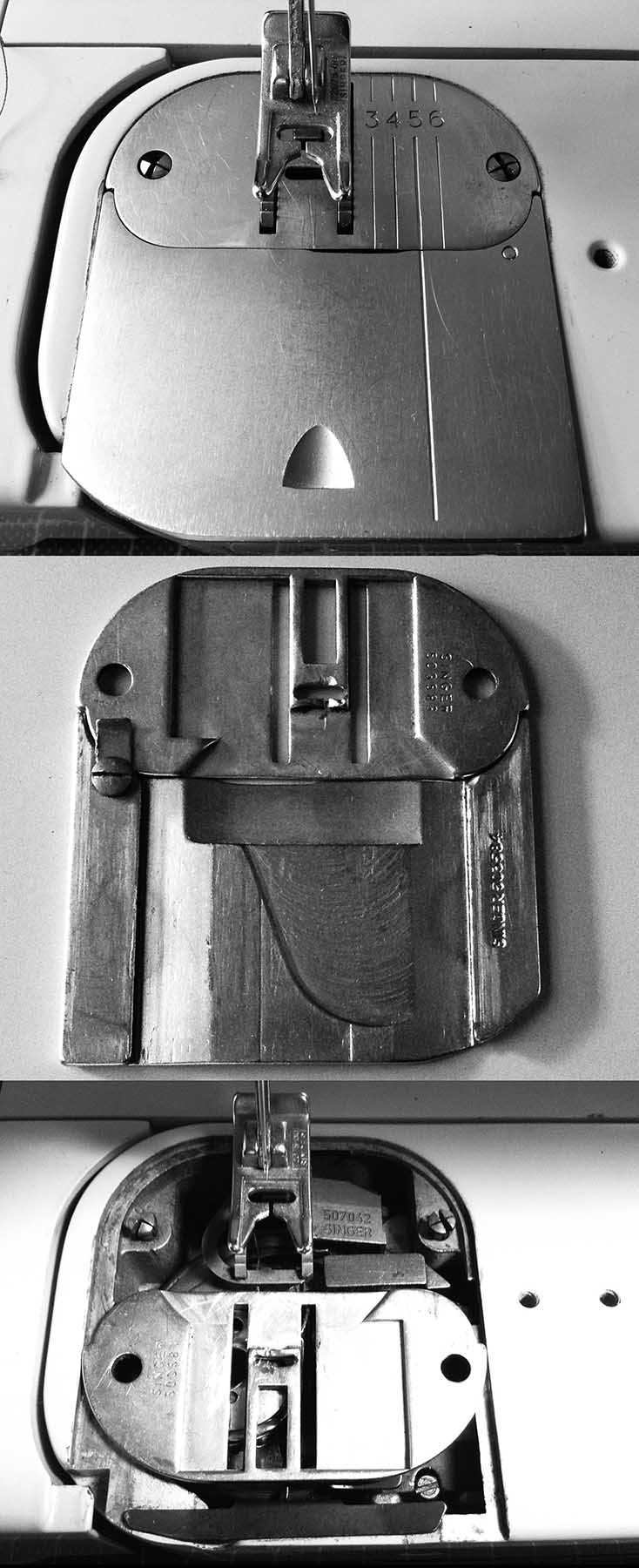

This is a composite photo of the chainstitch plate. Its serial number is 503601. I show it from three different angles – side, top and bottom, with the bottom photographed twice to show the range of motion in the swivelling piece that forms the chain stitch.

This photo shows the chainstitch. It is beautifully formed and not difficult to do.

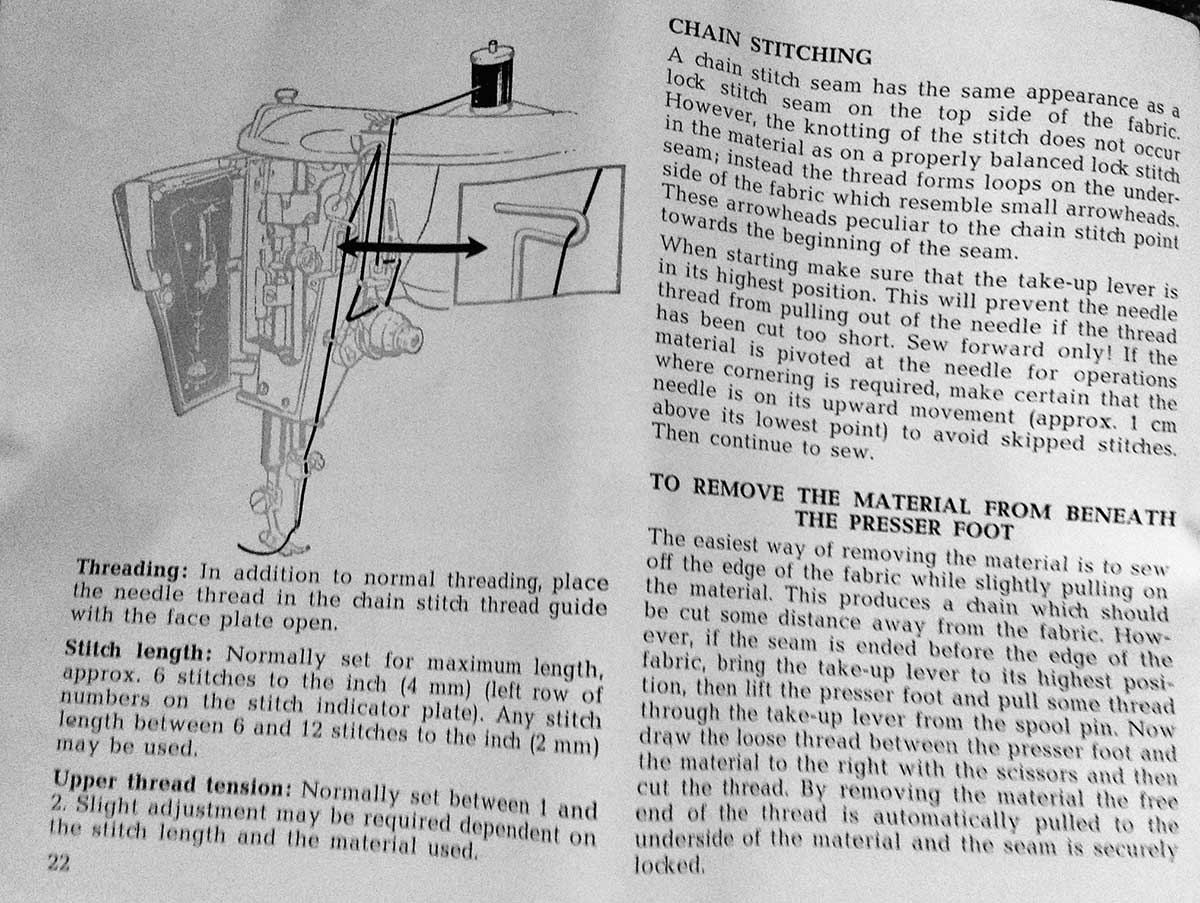

The bobbin is removed and the upper thread passed through the extra tension hook that is immediately left of the takeup lever.

I loosened the tension and used a stitch length of around 8 stitches per inch. Using a longer stitch length increased the likelihood of dropped stitches, as did a hesitation in pace whilst sewing.

The thread I used was just a cheap polyester but I was nevertheless impressed with the results and look forward to experimenting further with this as it was indeed the primary reason I wanted this machine.

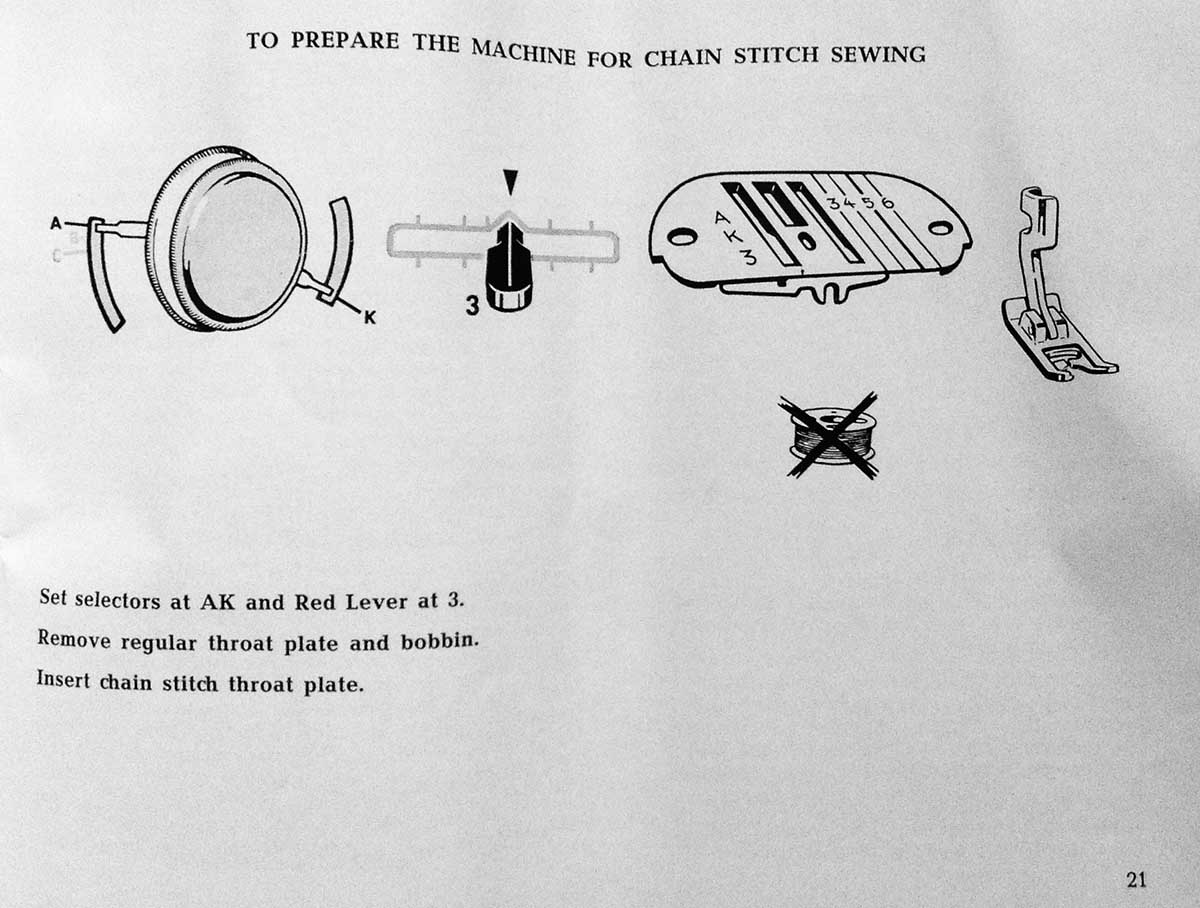

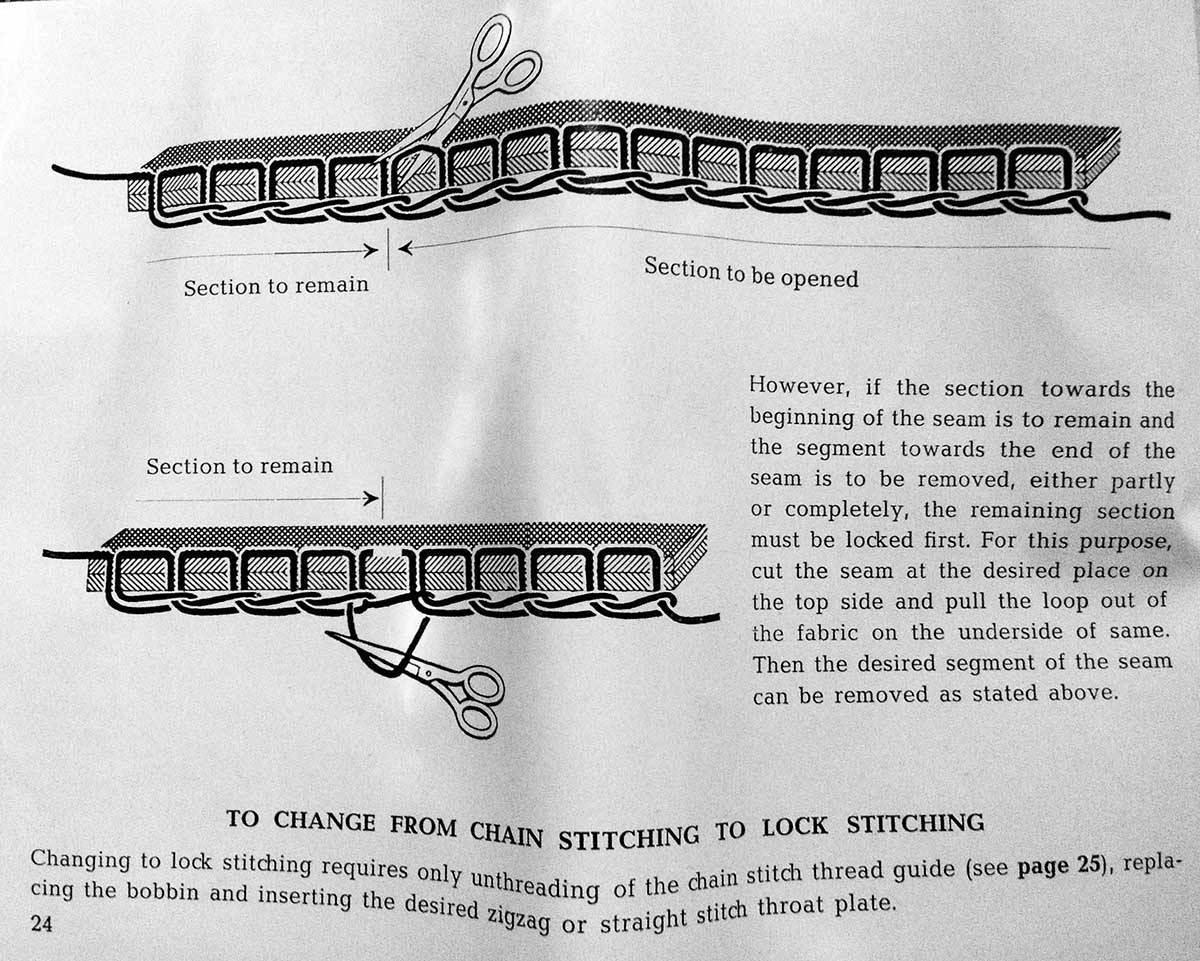

I will scan and publish a full version of the manual when time permits but in the meantime, here follow the pages relating to the chainstitching:

The top hat cams are the old style ones with two apertures in the brim. I am indebted to Barbara at Oldsewingear for her excellent blog post explaining the differences here: http://www.oldsewingear.com/blog/which-disc-is-which. I can confirm her advice that the 431 takes the ones she describes as Type 1.

These cams supplement the primary stitch patterns which are built into the existing, metal cam stack which sits below the area where the plastic cams may be fitted. The patterns are shown under the lid but further fine-tuning may be done using the stitch length too.

The manual advises to use the ‘Special Purpose Foot’ for these stitches as the raised area below the foot allows room for the depth of the satin stitches.

I do not presently have a straight stitch needle plate. I believe that its serial number may be 503582 but have no way of checking this. If any of you have one and can check it, please let me know.

I must draw attention to the fact that the lettering “AK3” appears on the top of the chainstitch plate as well as the straight stitch one so if you are seeking one or the other, do check that you are buying the correct one. The best and easiest way to tell them apart is that the chainstitch plate has a slightly oval needle hole and more notably a pivoting bar underneath that helps form the chainstitch.

Another common confusion that has come forwards in my research is the subject of replacement needle plates and whether the superficially similar T&S plates are compatible.

Instinct is telling me that I can see enough differences to make it unlikely that the T&S ones could be substituted but I can’t say for certain unless one came into my possession so that I could try it. Helen Howes (my favourite UK supplier) has several on her webpage and I can spot four main differences straight away, some obvious and others less so.

The 431 zigzag plate and the cover plates all have a rectangular area cut away on the underside, with a further two corners cut away further so that the base of the sides flared out at 45 degrees. Lining it up with the feed and the bobbin case I can’t see any reasons for this but I nevertheless can’t ignore it as possibly relevant for the plate to fit.

This photo shows the zigzag and straight stitch cover plates, both front and back.

This photo shows the area cut away from the underside of the bobbin plate.

Some of the plates for the T&S have measurements scored both sides of the needle hole. The 431 plates have measurements scored on the right hand side only, as shown here in this photograph of the general (zigzag) plate.

This photo shows the bobbin and needle plate together, top and bottom, showing how the two plates fit together. At the bottom of the photo, the underside of the needle plate is juxtaposed with the area which is covered by it.

Where the needle plate meets the bobbin plate, the curved sides of the 431 plates reduce width through a 90 degree turn. This edge is smooth. Some of the T&S plates are shaped similarly but have an extra piece of metal running below the edge of the bobbin plate, perhaps to improve the fit. I would be cautious of assuming that these extra pieces would marry up ok with a bobbin cover not designed to be used with it.

The holes for the clamping pins may be in a slightly different position; it is hard to tell. The back of the feed dog holes on the 431 plates looks as if it is slightly closer to the back edge of the plate than on the T&S plates. On the 431, the distance between the rows of feed teeth looks to be the same as between the feed and the back of the plate. Measuring confirms it – the distance is 2mm in both cases. These distances don’t look equal on the T&S plate.

Because it is impossible to accurately gauge size from photos, I have also measured the zigzag plate. It is 63 x 30mm. Mine has obviously suffered a bad needle strike in the past and I shall certainly replace it if I ever get the chance but as spares are rare, I’m not holding my breath for that…

The feet and accessories are all generic slant shank ones that I think will be able to be shared between any other slant shank machines.

The machine itself was in excellent cosmetic condition and did not need a great deal of cleaning. Despite this, I have taken all of her plates off and removed a great deal of fluff and a couple of needles from the base of the free arm. I was very happy to see how easily this may be cleaned out. The whole bottom of the free arm casing is a single piece, held in position by one bolt so it is very easy to access this area to clean and service it. The hook and bobbin case look at though they would benefit from a more thorough cleaning than I have been able to do so far but as I am unfamiliar with this style of bobbin and hook I will wait until I have educated myself a little further before attempting this.

The machine is now clean, oiled and ready to use. That said, I intend to run her in gently. It is certainly a good few years since she was last used and she has spent the last six months in a garage. Once I have properly run her through her paces I will report back with a post relating to performance, its neatness and quietness and how well she compares with my other machines.

I have not weighed her, but she is made from aluminium so whilst solid, is lighter than my cast iron machines and also lighter than my Bernina 830 Record, although similar in size. The extension bed is much easier to remove than the one on my Featherweight 222k. It is released by pressing a small button on the machine bed, close to the rear of the machine pillar and slides back on again very easily. The accessories are stored beneath an aluminium lid in the extension bed which opens up to reveal the compartment within, with space for the cams, oil, feet and attachments. The motor is housed vertically within the pillar and is easily accessed by removing the single bolt which secures the oil pan below. All in all it is very sturdily made and I am impressed.

Copyright of the blog owner 2017

21 Aug 2017 Leave a comment

in Book Reviews

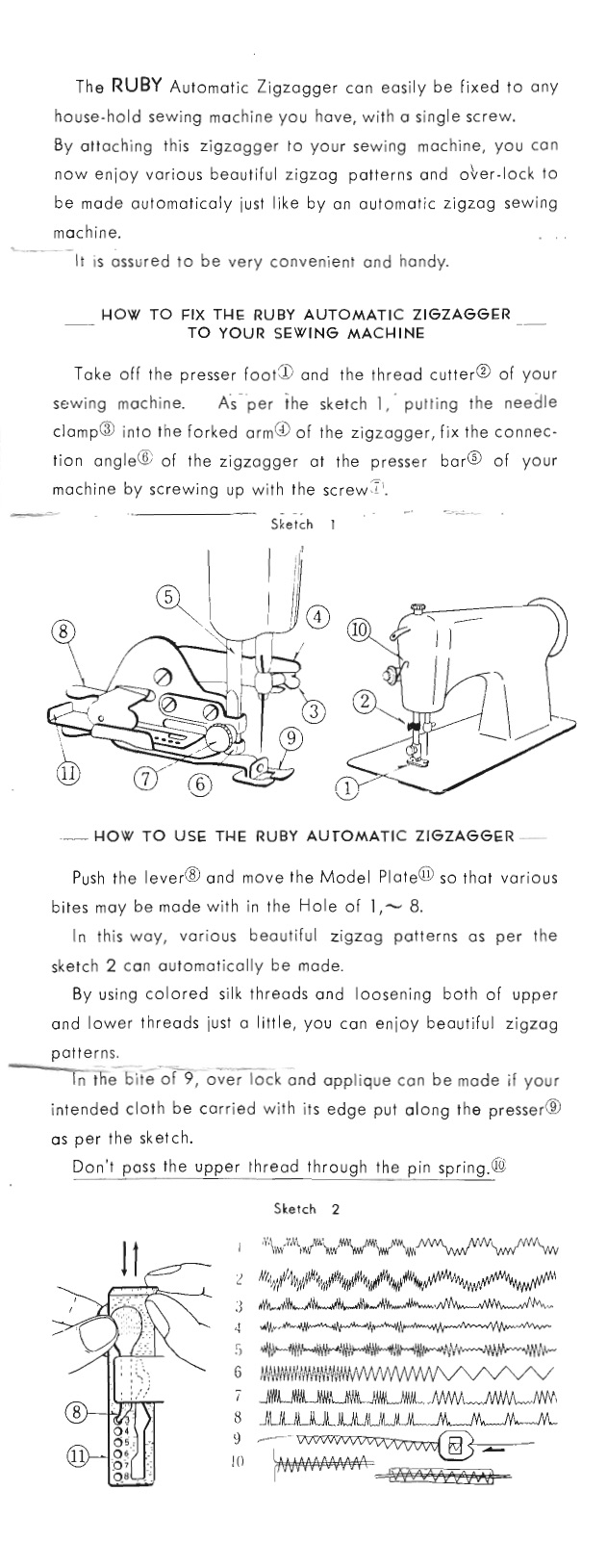

Originally I gave this a 5-star rating but I downgraded it on account of the quality of the photos. In common with many books of this era, the photos are grainy and lack contrast, especially through their mid-tones. Where the photos are intended to illustrate a process this makes it very difficult to interpret the picture as much of the necessary detail is hard, if not impossible to make out.

Elsewhere, the book makes good use of line drawings which ably demonstrate techniques such as construction of cord froggings and I think the book would have been better had line drawings been more widely applied. The artistic licence that an artist can apply to emphasise certain points and downplay others is especially useful when demonstrating intricate detail. The photograph labelled 19.13, for example, illustrates a technique of inserting a decorative band made up of short lengths of bias strips, sewn to a strip of paper. These short strips are then each nipped and stitched across to secure their cinched centres and give a decorative, bow-like finish but neither is this last point described in the accompanying text nor is it mentioned in the label and it was only by giving the photograph some intense scrutiny under a good light that I was able to discern exactly what I was looking at.

Leaving the photos aside though, this book has certainly surprised me, and favourably so. I very nearly left it unpurchased; a quick flick left me unmoved and fairly sure it would offer nothing new to my groaning shelves full of similar sewing books but it was only £2.99 so I decided to buy it anyway and prepare to give it some more attention.

I am glad I did. Truly. There is a lot of emphasis on couture techniques and good and thorough coverage of such essential, if supplementary skills such as pressing.

The contents list follows:

1) sewing equipment

2) the sewing machine

3) basic hand sewing stitches

4) pattern and fabric

5) pattern alterations and fitting

6) layout, cutting and marking

7) assembling dress for fitting

8) seam construction

9) pressing

10) methods of handling fullness

11) bias and its use in cordings, bindings and folds

12) buttonholes, buttons and fasteners

13) plackets, fly fronts and concealed closings

14) pockets

15) collars, necklines and closings

16) sleeves

17) waistlines and belts

18) hems

19) decorative construction

Appendices

A) sewing supplies

B) preparing a blue chalk board

C) directions for making pressing equipment

D) home methods for shrinking fabrics

Index.

Do give it shelf room if you are lucky enough to find it.

Copyright of the blog owner 2017

21 Aug 2017 Leave a comment

in Book Reviews

An ingenious little volume whose method is one of folding paper of predetermined dimensions into a grid which is used to plot the design. The method can be applied to a garment of any size as the proportions are calculated, for the most part, from a single body measurement: usually the neck measurement or the height of the wearer.

The garments covered are:

1) child’s chemise (two patterns)

2) woman’s chemise

3) woman’s yoked chemise

4) combinations

5) baby’s drawers

6) child’s knickerbocker drawers

7) girl’s knickerbocker drawers

8) woman’s tucked drawers – circular band

9) cottage pinafore

10) yoked pinafore

11) baby’s morning gown

12) baby’s frocks (two patterns)

13) child’s pelisse

14) baby’s flannel – baby’s shirts

15) bodice

16) night-dress

17) lined shirt, a back yoke for a tucked night-dress

18) single half-square gusset, circular band.

Copyright of the blog owner 2017

21 Aug 2017 2 Comments

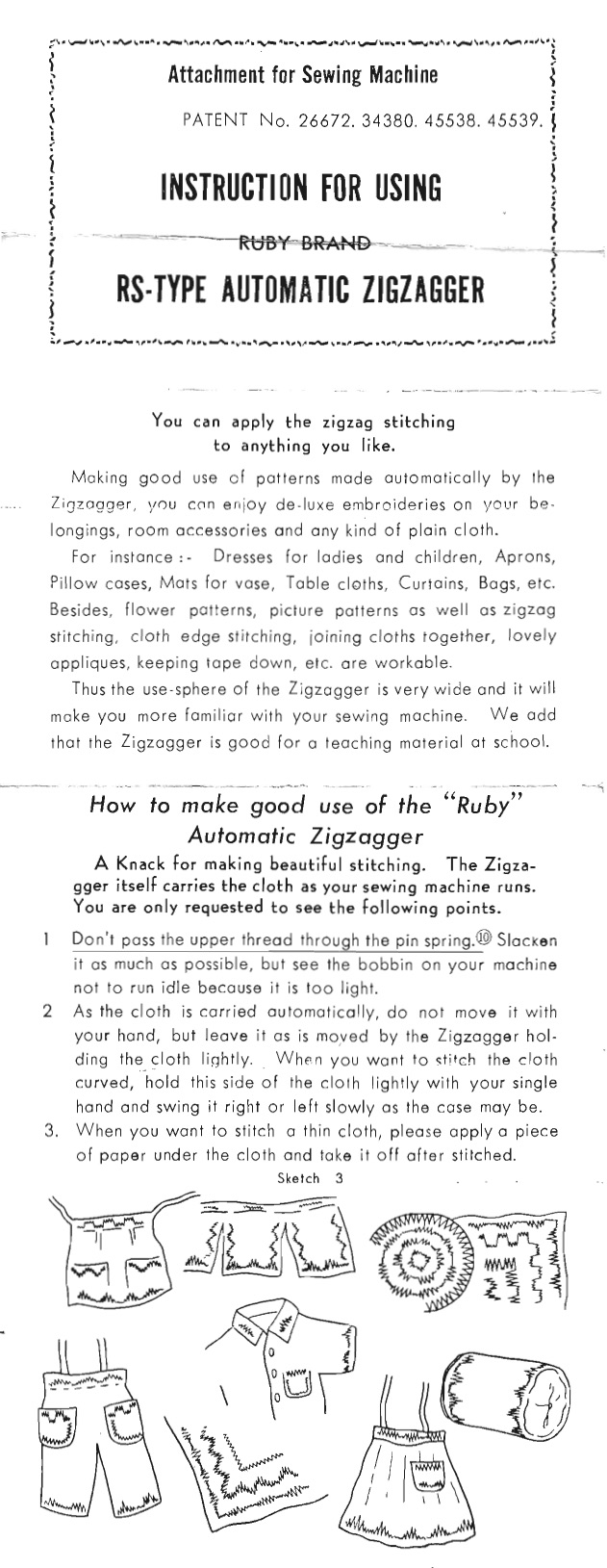

in Manuals

Following a request for the instructions for this, I’ve chosen to add them to the blog so that they are available to the wider community. I hope you all find them useful and enjoy using the attachment as much as I do.

Copyright of the blog owner 2017

12 Mar 2017 7 Comments

in Book Reviews

I own a great many books on dressmaking. Most of them assume construction knowledge or simply don’t cover it at all as they assume that the dressmaker will be using a commercial pattern, which will come with instructions which explain how to put the garment together and in what order. True, my older books do cover this but the emphasis is on hand sewing; if a machine is used at all, it is mainly for the long seams and the rest is very much hand-finished.

For those who seek to design their own garments and machine sew them, this leaves a frustrating gap in know-how and this is where this book really comes into its own.

As I mentioned, I do own a LOT of dressmaking books but this one really does have the best and clearest illustrations of complicated seam finishes that I have seen anywhere. Where some books use a series of stepped illustrations to demonstrate a technique, this one, by clear and well-thought-out diagrams, manages to make the entire process clear in a single picture. I can – at last – say that I understand a Mantua-Maker’s Seam…

So, if you need to know how to insert an under-arm, diamond-shaped gusset or the proper method of inserting godets, this is the book you need.

Fly fastenings, collars, plackets, cuffs and zips… it’s all here.

I can’t think of anyone who wouldn’t benefit from reading this. It has a really good ratio of text to diagrams, the text is well written and easy to follow – not pitched too high – and it has a good index. It’s a handy reference for design students, home dressmakers and professionals alike.

Copyright of the blog owner 2017

12 Mar 2017 Leave a comment

in Book Reviews

Definitely one for the girls as there are no boys’ garments included here. As a mother of a boy this was naturally a little disappointing but other volumes of similar era exist which do include boys so I was not entirely bereft.

The text is clearly written, the subject matter covered comprehensively and the line drawing diagrams are particularly well drawn, showing clearly the needle position, stitch sequence or whichever detail or method is being illustrated.

I am always impressed by the amount of practical and sensible tuition contained, so succinctly, in these older volumes. All the basic rules are here, with thorough explanation and examination of techniques, stitches and materials and – more pertinently, in my opinion – on how to choose which to use in a given circumstance.

Returning to the diagrams, those relating to the pattern cutting are especially clear. The method used in this book is especially suitable for the inexperienced or unconfident pattern cutter. The starting point is a piece of paper of set proportions and by folding this paper a number of times both vertically and horizontally, the resultant grid is used to plot the pattern according to the accompanying diagram. (Those interested in this method should also seek out the book “Pattern-Making by Paper Folding”, by Miss F Heath, published by Longmans, Green and Co in 1910.)

Unlike many contemporary needlework volumes, there is no mention of mending; it is purely making.

I do not think that the patterns lend themselves to modern interpretation quite so readily as the simpler garments covered by “Simple Garments for Children” by M B Synge but with suitable modification (slight modification to side seam silhouette, fullness arranged as pleats rather than gauged gathers, etc) there is plenty of scope for practical application and even if one ignores the patterns altogether the explanation and illustration of technique makes this book a very worth while purchase.

There is a section specifically covering dolls’ clothes and bedding which, whilst originally intended as reduced scale practice pieces, will appeal equally to those interested in producing dolls’ clothes from patterns which are correct for the era of the doll.

Copyright of the blog owner 2017

21 Mar 2014 1 Comment

in Book Reviews

Large format, hardback book measuring 11″ tall x 8″ wide x 1″ thick. Green boards (1945 reprint of 1942 original), 253 pages.

I have an increasingly extensive library of vintage sewing and needlework books and confess that this has to be just about the best I have seen.

Not only is it beautifully presented but unlike Mme Trois Fontaines’ Dress Design and Margaret Ralston’s Dress Cutting (who both cover a similar era and similar subject matter) Pepin goes one step further and gives a proper discussion to the matters of proportion and good design and encourages experiment and the development of a well-trained eye.

Pepin is also extremely comprehensive – more so than Fontaines and Ralston. She is similar in content to Natalie Bray except that she gives more consideration to the process of good design and the illustrations are, to my eye at least, more pleasing and easy to interpret. Unlike Bray, Pepin is also contained in a single volume.

The front bodice draft is a very simple, single-dart pattern which is easily adapted and lends itself very well to experimentation.

The chapter headings are:

1) Pattern Designing

2) Slopers

3) Hip Length Patterns

4) Sleeve Patterns

5) Adapting Patterns

6) Capes, Ties, Neckwear and Scarves

7) Collars

8) Skirts

9) Slacks, Shorts, Culottes and Bathing Suits

10) Lingerie

11) Coats

12) Children’s Clothing

I had to wait a long time to find a hard copy for a reasonable price but would certainly recommend this book to anyone wanting to study not just pattern cutting but clothes design as a whole.

Copyright of the blog owner 2014

21 Aug 2013 2 Comments

in Mending

The first job for today was to finish what I first started last night; darning the splits in my husband’s jeans. Both the back pockets had pulled away the fabric onto which they were stitched and all four top corners needed to be reinforced and the missing threads darned over.

The particular challenges with this sort of mending relate to the different densities and thicknesses of the fabric layers. Sewing in close alongside the pocket edge is difficult as the foot is naturally deflected by the vertical edge of the pocket piece and when sewing back and forth across the top of the pocket corner the foot is required to rise up and over the ramp in both forwards and reverse. I could have minimised the deflection issue by using my new ‘Slim Jim’ foot but because of the need to ride up and over different thicknesses I chose the normal presser foot as it is hinged. I minimised the deflection by loosening off the presser foot pressure.

The job was performed on my usual machine, the electric, 1939 Singer 201k and a size 12 needle. The needle ought to have been a 14 or a 16 for this sort of fabric but as I presently have only 10s and 12s I simply went slowly over the thicker sections, occasionally just ‘handing’ it for a couple of stitches where it crossed the thread bars and had no trouble. The thread in both bobbin and upper was a cone of core-spun overlocker thread which I always use for these jobs as it is a good match for faded denim. Because of the need for cones to feed off vertically I run the thread from a large, industrial-type thread stand bought from Barnyarns.

Copyright of the blog owner 2013

17 Aug 2013 2 Comments

The measurement required: – The size round the neck of the intended wearer. The collar is one-and-one-sixth of the neck. All the other measurements are derived from it. The body of the shirt is made in one long piece three-and-three-quarter times the collar length, folded nearly in half, the front being only one-quarter of a collar length shorter than the back. The width of it is one-and-a-half the collar length. Where the fold comes is the top of the shirt.

To Cut The Pattern.

As the back and the front of the body of the shirt are alike at the top, in making the pattern it is only necessary to cut the back-half. Take a piece of paper two collar lengths long, and one-and-a-half the collar length wide; fold it into four each way. Keep it folded in half lengthwise, and curve out the arm-hole from one-third of a division across the top, to the point of the first division downwards. Keep the piece you have curved out.

To Cut The Sleeves.

Take a piece of paper once-and-a-quarter the collar-length long, and two collar lengths wide. Fold it lengthwise into eight. Open it out, and then fold and cut a diagonal line through the two middle divisions. Take one of the pieces and fold it down the middle, as shown by the dots, by making the straight side lie on the sloped side. That will leave a single piece of the paper at either end which must be cut off. A small piece must be sloped off the bottom to prevent too sharp a point, and the top must be shaped. Use the piece you cut out of the armhole as a guide for that, as the top of the sleeve and the armhole must be alike.

To Cut The Neck.

The neck should not be cut until the shirt is partly made. A pattern the exact size of the piece required to be cut away can be made by cutting out a circle, the diameter of which is one-third of the collar before the turnings are allowed for, and then flattened a little (rather more than is shown in the diagram) at the top and bottom, and marking a line across it about one-eighth from the top. The following directions for making up the shirt are given, because they will simplify the work of teaching a large class. They have been found useful in the London Board Schools, as a great many shirts of this pattern are made every year for the Industrial Schools.

The Lining.

This should be put on first. Open the shirt flat, and then tack, and afterwards hem on the lining, giving exactly one-half of it to the front, and the other half to the back. Leave unhemmed three-quarters of an inch at the ends, until the seams are finished, in order that they may not be interfered with.

The Side Slits.

The side slits must be the same length as the armhole, measuring the front breadth of the shirt.

The Front.

The opening for the front must be cut about half-an-inch to the left side of the shirt, and must extend half way down the front.

The Front Piece.

This must be carried down from an inch to an inch and a half below the opening.

The Sleeves.

The sleeves must have the straight part to the front of the shirt.

The Sleeve Slits.

The sleeve slits must be half the length of the wrist-band.

The Wrist-Bands.

The wrist-bands must be divided into three, and all the gathers must go into the middle third.

To Cut the Neck.

Fold the front over as it should be if buttoned, and place the neck pattern on it so that the crossway line may meet the top of the shirt, and point A touch the middle of the front. Cut round it, leaving nothing for turnings.

The Gussets.

Gussets must be put in at the top of the sides and sleeve slits.

Copyright of the blog owner 2013

18 Mar 2013 2 Comments

in Projects

When I was first at college, studying for my fashion diploma we had to produce a folder of samples. This served both as practice and reference and I have often thought about it and how useful it was for me as a beginner. The subject has occurred quite a lot in conversation so I’ve been prompted to put together a post of suggested practice pieces which might prove useful to anyone wanting to do the same. The important thing is to label everything well and to list the stages involved – either by including examples of each point or by listing the steps taken to reach the finished sample shown.

Stitch Samples

You will need: plain cotton lawn, medium-weight cotton, cotton jersey, coarsely woven fabric. All fabric should be plain – patterns make it too hard to see the detail of what you have stitched. Stickers and pen to label the fabric with. Tension should be set at between 4 and 5 unless stated otherwise. Match the thread colour to the fabric as closely as possible.

Stitch Length Exercises

Each machine will vary in the range of stitch lengths (mine are old machines and are incremented in 6, 7, 8, 10, 12, 15, 20 and 30 stitches per inch) but for simplicity’s sake I will suggest sewing with 1, 2, 3 and 4mm stitch lengths although you may of course include samples for 1.5, 2.5 and 3.5mm if you wish to do so.

Seam Examples

Fabric – cut a 20cm square of fabric into four equal strips, cut each strip in half and press them. This will give us eight fabric strips 5 x 10cm. We will sew strips together in pairs, using different stitch lengths on each to show how it looks and behaves when pressed open.

Seaming and Hemming curves:

Seaming stretch fabrics

Hems

Buttonholes & Buttons

Darts, Gathers & Ruffles

Pleats and Tucks

Pockets

Zips and Fastenings, Openings & Miscellaneous

Copyright of the blog owner 2013

01 Mar 2013 Leave a comment

Looking through my old needlework books I found the attached and thought it an excellent resource well worth reproducing and sharing here.

The jpeg is necessarily in quite low resolution to meet the file size requirements for attachments so I’ll transcribe the text here:

“The sequences for making-up on the opposite page naturally have to be altered for jackets and complicated garments. Especially important is the frequent pressing, which has to be done after every seam is sewn. All embroidery should be worked before the garment is made up, unless the design crosses the seams, in which case it is better done afterwards.

The Sequence for Sewing a Dress

1. Put in darts at back, front and side. Draw out tacking threads, and press.

2. Machine side seams, draw out tacking threads, and press. Any fastenings can be left until last.

3. Machine shoulder seams, draw out tacking threads, and press.

4. Machine skirt seams, pull out tacking threads, and press.

5. Join skirt and bodice, remove tacking threads, and press.

6. Machine sleeve seams, remove tacking threads, and press.

7. Put in sleeves, press and finish off.

8. Finish off neck.

9. Finish the wristbands.

10. Turn up the hem, press all seams again, put on trimmings, and press finally.

The Sequence for Sewing a Coat

1. Machine darts at front, trim and press, shrinking material at the points.

2. Machine underarm and shoulder seams, and finish them if the coat is to be unlined. Press.

3. Cut canvas or linen interfacing, and tack to wrong side. Join to coat and outer edge of under collar. Press.

4. Join under collar and coat – trim seam and press open.

5. Make bound buttonholes.

6. Join coat facing to collar.

7. Join collar and facing.

8. Turn facing and collar inside, tack into position.

9. Turn up hem.

10. Make pockets.

11. Cut out and fix in lining.”

From Weldon’s Encyclopedia of Needlework (undated but looks 1940s. Red boards. Hardback. Boasts nearly 2000 illustrations. I also have an earlier version dating from the 1920s which is much smaller and with only 500 illustrations. That one has pale green boards. The two volumes are not at all alike and the contents equally valuable.)

Copyright of the blog owner 2013

14 Feb 2013 Leave a comment

in Book Reviews

Published by Odhams in 1946 this is a hardback book with a grasscloth cover, measuring ten by 7 inches and printed on quite thin but good quality, silky paper. The text is well written and is liberally scattered with pen and ink diagrams, very well drawn and clearly illustrating the techniques they demonstrate.

Some of the text is amusingly obsolete – my husband and I were equally amused by the “When You Mend for Men” section which commences with the observation that “every new husband is happy about the first button that comes off. His bride will sew it on for him and he will revel in this special attention” and which later, mentioning the sense in putting a price on one’s time and keeping a notebook of time spent and money saved sets as an example the “one woman with husband and three children to sew for learned to mend, took the necessary time to learn to do it well. At the end of a year she showed her husband she had really saved enough to warrant his buying a piano for her”.

Anyone familiar with the author won’t be surprised to hear that this really is an excellent and very comprehensive book and whilst the skills taught herein are hardly exclusive, the pleasing layout of this book together with the clarity of the diagrams makes it easily one of the better books I have encountered.

It truly does start with the basics. This is certainly the first time I have seen close-up diagrams showing how to thread a needle but each of us has to start somewhere and with people less likely than ever before to have learned these skills from a relative or at school it is not inappropriate to have them mentioned here.

Indeed many of the finishings and techniques covered as standard subject matter here now find themselves promoted to the lofty status of “couture” techniques and are overlooked by many ordinary sewing books whose aim is to use the sewing machine almost exclusively. The example of factory-produced goods too frequently leads us to believe that items are “homespun” and inferior unless made entirely by machine and it is time we debunked this.

Even though this is a book specifically about mending there must necessarily be some overlap with books on dressmaking and general needlework so seams, hems, embroidery stitches, darts, gathers, tucks and ruffles, pleats, godets, neckline and sleeve finishes, plackets, fasteners and buttonholes are all covered here but often with a slightly different bias – bound buttonholes are, for example, promoted as being an excellent way to refurbish a buttonhole frayed out of shape too badly to be simply reworked in buttonhole stitch.

There is a handy section dealing with how to recognise the fibre content of cloth and also a good introduction to the sewing machine and its attachments.

In keeping with a sense of proper economy and foresight there is discussion about reinforcing areas prone to wear and tear and also the particular method used in mending each of a variety of different tears – invisible darn, slashes, reinforced darn, one-way darn, corner tear, runs in knitwear, cross-wise splits in knitwear, stocking grafting and irregular machine darn.

Patches are shown in variety; including some which are cunningly designed to look like a design detail whilst in fact hiding a stain or a tear.

Underpinnings receive a lot of coverage; the reinforcement and renewal of straps and fastenings, how to disguise minor repairs, mend frayed edges, deal with broken fagotting, seams and worn elastic, reinforce where bones and wiring pushes though.

Some things, like repairs to cuffs, collars and pockets I have seen before but others, such as gloves, ties and belts are less common as is the very comprehensive coverage given to the repair of blankets, pillowcases and sheets, including the hemstitched variety which often tears along the hemstitching.

Laundering is also mentioned: stain removal, washing, ironing, cleaning and pressing, as well as an area akin to dry cleaning referred to here as “Freshening” but do indeed treat this with caution as the chemicals are indeed eye-watering and the reader must be responsible in his or her own research into the chemicals involved before attempting to follow any of the advice in this section.

The final part of the book deals with refashioning clothing – of refreshing worn areas, updating them and in picking them apart and reusing the cloth. It advises the seamstress to look carefully at each garment and assess its merits before deciding upon its fate: first considering whether some refurbishment, recutting or readjustment could do anything for it. Next consider whether, when done the garment would do anything for you!

If that seems hopeless, either give it away or else rip it apart at the seams and reuse the material for something different. I have to say I snorted somewhat at the part where the author advises against the home sewer attempting to draft her own patterns, opining that it “requires equipment and experience beyond the home sewer’s ken.” I do happen to have had the benefit of professional training in pattern cutting but certainly don’t agree that it is beyond a home sewer to learn the same skill.

Ideas follow as to the sorts of project which could be attempted for different garments – evening coats into skirts, jackets, even boudoir cushions! Men’s shirts are particularly prized as being a suitable basis for children’s shirts, blouses, aprons and pinafores. The author sets a pretty tight schedule, mind: to produce a pair of trousers or a dress from reclaimed fabrics will take six hours by her estimate: one for ripping and pressing, one for cutting, one or possibly two for basting, half an hour for fitting, half and hour for adjustments after fitting, one for stitching, half an hour for buttons and buttonholes and half an hour for a complete pressing. The author does concede that this represents a highly concentrated schedule, as she puts it “making every stroke count”.

Coats merit a section all their own – trimming with new fabric on pockets and revers, recutting, remodelling and relining.

Dresses also receive a chapter all their own: suggestions being made to sew in entirely new sections of fabric where areas are looking worn and to use even the smallest piece of fabric to add a cheerful touch to cuffs, pockets and other small details. Eyelet embroidery, velveteen and taffeta are all shown used in a variety of ways to liven up old items as are lace, tassels and ribbons.

When cutting down garments to be remade for children the author suggests using the following checklist:

1) Is the fabric worthy of my time?

2) Is it easy to wash and keep in repair?

3) Is it worth the expense of needed new material?

4) Is it in suitable colour and weave for a child?

5) Is it right for the child who is to wear it?

One caveat – this section advises using tie fasteners of narrow tape or ribbon or wider ties of material for baby’s first garments and tot’s dresses. Please be aware of strangulation risks when having any tie on clothing intended for babies and small children.

Copyright of the blog owner 2013

11 Feb 2013 Leave a comment

in Book Reviews

A well written book illustrated clearly with black and white photographs showing a very comprehensive range of stitches, techniques and articles.

This is not a book which includes patterns which may be scaled up and used but it does include line drawings which provide sufficient visual information about fullness, style lines etc for a competent pattern maker to draft a similar garment – this being especially true of the childrenswear, which examples are particularly engaging, especially the middy blouse and rompers.

One of the peculiar strengths of these older volumes is the particular attention give to construction. Possibly because of the weightiness of full-length skirts cut from woollen cloth the waists were not simply set into a modern style of waistband but were instead often hung from a strong, internal waistband of shaped petersham or similar rigidly woven tape which allowed the weight of the skirt to be carried not by the fabric of the costume but by the abdomen of the wearer.

Similar attention is given to the fitting of a corset cover – the care with which the garment is quartered by twin rows of gathering threads which are then gently pulled up and shepherded into the correct position is a study well worth revising today for any garment in which gathers are to form the main shaping over the bust.

Suffice it to say that all of the usual hems, stitches and seam finishes are described and illustrated and good suggestions made for correcting and disguising ill-fitting portions of garments such as a sleeve too long above the elbow or tight across the forearm.

In conclusion this is another very comprehensive volume and one I would not wish to part with.

Copyright of the blog owner 2013

11 Feb 2013 Leave a comment

in Book Reviews

A highly informative volume introducing a full introduction to the sewing machine and its attachments, including a demonstration of using a veining foot to make picots which I have never seen before and am very glad to know. The book lists suggested items of equipment for sewing, pressing and the mending basket. As well as the usual, ubiquitous instructions on where and how to measure, instructions are given for padding out a dummy and fastening a padded arm thereto, all valuable lessons when trying to achieve a good fit either in shop-bought, or home drafted patterns.

Given that this book is not written as a drafting book the instructions for creating and adapting basic blocks are really very good; simple to follow but easily comprehensive enough to form a firm basis for most dressmaking and furthermore, patterns are shown throughout the book, drafted against a grid for easy transferral.

A good appraisal is given to fabrics, their widths, quantities and qualities as well as their suitability to various styles.

Reading the chapter on pressing I was again struck at how sensible and comprehensive was the advice given. Clear illustrations showed real-life examples of what was being discussed, including the use of a pressing cloth, using a padded rolling pin to press open seams and the use of the tailor’s ham in pressing sleeveheads. You will certainly learn all the correct methods here and your sewing will be the better for it.

The chapter on fitting is equally clear. I can’t claim that it covers any more or less than other books on the subject but somehow the diagrams get right to the very heart of the matter and make it simple to compare the problem in hand with the issues illustrated and find out how to solve it.

The chapter on sewing details once again cuts through the unnecessary and gets right to the heart of the matter – namely how to deal with all those awkward, non-standard fastenings like leather buttons and the bone ones which need to be removed before washing. I have also never seen such a neatly illustrated description of inserting zips – truly this book is an absolute gem.

The Lingerie chapter supplies patterns for some truly elegant and timeless pieces – a bias cut nightdress, a long sleeved nightdress, a princess slip, camiknickers, brassiere and knickers but be warned that the bra in question is a dainty little number best suited for nothing beyond a B-cup and of a simple, rounded shape. You won’t learn how to draft a bullet bra here (although in truth that would not be hard to do, simply by straightening the vertical seam lines a little and reinforcing with the requisite concentric stitch lines).

This book truly does attend to precisely the right things. Rarely have I ever seen bound buttonholes, tucks, pleats, piping, rouleau loops, cuff openings and bound hems so nicely and plainly described.

The same applies to pockets. Bound pockets, welt pockets, slot pockets, patch pockets, flap pockets. All well described and beautifully illustrated.

How to make a belt? It’s here, with many pretty ideas on how to finish and fasten.

The chapter on collars shows very clearly how the different types are drafted from the bodice blocks laid together at the shoulder seam. Each has a particular profile, depending on how high or flat it is to lie and the different shapes are very well shown here.

Sleeves are quite narrow and sculpted, as to be expected from this particular era but other types are discussed also. Useful tips such as the application of interlinings, stiffeners and special tight linings into the sleevehead of a puffed sleeve to prevent it migrating down the arm are again all subjects new to me and very welcome. Another new tip for me was that of how to cut and attach a shaped interlining into a sleeve; cut half the breadth of the sleeve, rounded at the top and sewn into the lining it provides extra warmth.

Pattern diagrams are given for the following garments, with extremely detailed instructions for cutting, fitting and making up: one-piece dress, princess style; cardigan suit (a neat suit with shaped jacket and straight skirt with kick pleat); blouse with rever collar and bishop sleeves and the items of underwear mentioned earlier.

The childrenswear chapter is truly a delight as it covers a far better range than the usual rompers, dress and knickers. There are proper instructions for the drafting and making of a woollen blazer, suggested to be best suited to a boy of ten to twelve years but easily adapted to other sizes besides. Knee-length trousers to match are also covered here and the photo is simply delightful – the shorts are shown knee-length and fastened with a snake belt. This is such a timeless accessory I have photos of my father (born in 1919) wearing one when he was about ten and my own little boy, aged four wears one even now. For girls, a neat, pleated skirt with inverted box pleats is shown for a schoolgirl. It is cut a couple of inches above the knee similar to gym shorts and is worn with a blouse made to the same pattern as the boy’s shirt but fastening the other way of course. Also for girls, a pair of ‘School Knickers’ which resemble athletic shorts, being of a simple shape gathered onto a band of elastic at the waist. It is suggested that these can be made in a thinner fabric for wearing under party frocks in which case the leg edges could be finished with a fabric frill or with lace. There follows a plain, cotton print frock with a high neck, simple collar, elbow length sleeves and waist sash, cut above the knee and very ‘youthful’!

There is just the one dress for a baby – a classic, knee length design with short puffed sleeves and a skirt gathered onto a yoke under the arms.

The final articles of childrenswear are again refreshingly practical – a darling set of unisex pyjamas. The jacket is made to the same pattern as the blazer, but fastened up to the neck and the trousers made from the shorts draft, lengthened accordingly. A modified pattern is described wherein the bodice and trousers may be combined and feet added to make a sleepsuit for a younger child.

The final chapter deals with mending, patching, darning and the setting in of the small triangular gussets into the bottom of side seams.

This is, in my opinion one of the most comprehensive texts I have read and should you buy only one book on home dressmaking, this would be a very good one to choose.

Copyright of the blog owner 2013

11 Feb 2013 Leave a comment

in Projects

The author explains that this, the second edition differs from the earlier only in that a few minor alterations have been made and the index made more comprehensive. I mention this as often books are substantively enlarged and revised between editions, photographs and techniques being updated in line with changes in fashion and technology but as childrens’ wear changes little this is not the case here.

I must say right at the start that anyone wishing to see full drafts for contemporary fashions will be disappointed as this book supposes that the mother will buy a pattern, not make it so the subject matter is limited to the cutting out, making up and finishing only.

This should not be held against it though as the book has much to recommend it, containing many good tips not often considered today such as allowing for growth in the garment so that its usefulness is extended.

The book itself is printed on good quality, silky paper and has aged very well with no sign of deterioration or discolouration at the edges and corners. The illustrations number 100 and are all greyscale photographs. While they are quite charming (lots of ‘Marcel waves’ in the figure shots, suggesting their origin a full decade earlier) they are quite dark and do not give such a clear demonstration as a line drawing would do.

The book is much more wordy than many but Agnes Miall writes in a confident and easy style and it is by no means hard to follow.

Agnes assumes no prior knowledge of sewing and helpfully suggests a detailed list of sewing items required and gives tips also on good working practices and the need for a well-lit spot and the necessity of taking regular breaks from sitting, especially when pregnant.

This book truly does start with the basics, including a basic education in the three different types of stitches – namely joining, hemming and edging – which will be encountered and reassures that the twelve stitch types contained therein will, between them, serve every purpose.

Having covered those stitches the book moves on to the first garments; the baby’s layette. Again expecting no prior knowledge, it gives a list of the average layette required:

4 woollen vests (bought or home knitted

4 nightgowns

4 flannel petticoats

4 dresses (daygowns)

1 large carrying shawl (bought or crocheted)

2 to 3 dozen Turkish towelling napkins (bought ready made)

3 pairs of bootees (knitted)

1 sleeping bag (for the pram)

2 bonnets (or crochet caps)

2 matinee coats

1 or more silk or muslin robes, with nainsook petticoats to wear beneath.

Chapter IV deals with cutting out and marking, emphasising the correct methods of pinning, use of the straight grain, tacking and arranging the pieces on the fabric, cutting out and marking the seam allowances through between the two pieces. It may all seem a little long-winded compared with modern methods but I can confirm from personal experience that time taken in careful preparation is never wasted as no number of flawless seams can salvage a garment which twists due to being cut slightly off grain.

The next chapter teaches what seams should be used to join the various portions of the garment and instructs on the matter of plackets, facings and bindings and how to construct and apply them although some of the suggested applications, such as a drawstring pulling in the full circumference of a wide neckline, would be frowned on now as unsafe so do please exercise some caution if using this book as a resource for making similar garments.

The garments covered in that chapter include flannel petticoats, a sleeping bag, day dresses, petticoats, matinee coats and bonnets. Suitable fabrics are suggested for each as well as the general instructions for making them up.

Chapter VI covers trimmings, including bias binding (home made), tucks, lace trimmings and insertions and finally hand embroidery. As previously mentioned the greyscale photographs represent the finished item rather better than the technique being employed but nevertheless the text provides perfectly good instruction.

Clothes for the Toddler covers some good ideas for making bibs out of table linen and face cloths; feeders (larger, plainer bibs), sleeping suits and rompers, knickers for either sex and finally leggings. The subject of correct pressing is also discussed here.

Chapter VIII deals with the subjects of growth and of fitting. In brief, extra turnings are suggested so that the garment may be let out as the child grows.

Very good advice is given on altering patterns, specifically on the subject of where and how to add the extra. The book warns that unless the alteration is a small one, simply adding to the seams will frequently just throw the whole pattern out of proportion. It advises instead to think of the body as a series of definite segments so that it is simpler to see where the extra needs to be added and apply it accordingly.

Hints are given as to placing hidden tucks which may be let down later and also of extra depth hidden up inside a yoke which may simply be unpicked and reset lower down when the need arises.

Finally in this chapter, a whimsical topic called the “Language of Pins”, used when fitting, which promotes the idea of angling pins according to a set formula – pins placed vertically along a hem means that the hem is too short between the pins; placed horizontally means too long and should be turned up deeper to the level shown by the pin; two pins pointing diagonally outwards means to let out whilst the opposite means to take in. Pins set in a cross show the exact position of a button or other fastener. That is the only one I was previously familiar with.

Dressmaking for Little Girls introduces some more advanced methods of facing and finishing hems, including the correct method of hemming a square neckline, the making up and setting in of collars, bands and cuffs and pleats. Some general guidance is given on the subject of Gym Tunics.

Trimmings such as frills and gathers are covered next, including some instruction in gauging, which is the gathering of the fabric in parallel folds such as is done when preparing fabric for smocking. Some practical ideas are given for decorative trims made from simple braid – ruching, shelling and box-pleated ruching – and the use of fur and fur fabrics is also given special mention and while the use of real fur has quite properly fallen out of favour in modern times the instructions given for the treatment and handling of fur fabric are still valid today.

Hand embroidery fills the whole of the next chapter but because this is such a ubiquitous subject I shall not waste words on it here. Suffice to say that the usual stitches are covered – lazy daisy, smocking etc.

Chapter XII covers tailoring for little boys. Boys’ clothing is generally covered less comprehensively than clothing for little girls so any mention at all is worthy of especial notice.

Knickers are the name used for what we would more usually call shorts these days and these are the first item mentioned. I concur with the author that these are very simple and quick to make and I love the ideas she gives for fastening them onto the ‘bodice’ (or shirt, in modern terms). All very sensible for keeping a child neat and trim at the waist yet allowing for easy and quick access when changing a nappy or potty training. For the slightly older boy, instructions are given for the making up and setting in of pockets and fly-fastenings. Pyjamas and shirts are also covered in this chapter although remember that no patterns are given; it is simply the order of making up and the appropriate seams and finishes which are covered here. Hand-sewn and bound buttonholes are introduced here and the introduction of gussets into the end of the cuff opening placket and the bottom of the side seam where the shirt tails commence.

Chapter XIII, trimmings for boys’ clothes, admits in the very first sentence that it is a very short chapter, as boys whose clothes are over-trimmed will soon be teased by their peers so the author quite rightly urges restraint. She suggests that up to the age of three the clothing may be as ornate as the mother chooses and even up to the age of four or five rompers may possess small amounts of smocking or laid pleats are acceptable but in today’s society I would advise that these age limits are shunted downwards quite considerably! Some of these details have survived better than others though: whilst I cannot think of having my son have smocking at any age, pintucks and laid tucks I would be perfectly happy to introduce in a linen or cotton shirt at any age up to about seven or eight. The author suggests that while hand embroidery is ok up to the age of four or five, much less should be used than on a garment for a girl of the same age and neat topstitching, tailored details and belts, collars and cuffs trimmed in a plain, contrasting colour is a better choice for little boys. Unexpectedly, embroidered buttons are introduced at the end of the chapter.

Dressing the older girl introduces the subjects of darts, flimsier fabrics, french seams and methods of supporting the fabric when sewing flimsy fabrics such as chiffon.

Chapter VI covers another of my favourite topics, that of mending and cutting down of clothes.

Preventative mending is covered very well, with suggestions for almost imperceptible reinforcements to stockings, socks and jersey elbows and the seats of pants. Also suggested is the use of linen tape behind any area receiving strain from buttons and the suggestion to reinforce by extra stitching any button or fastener in a bought garment, making certain to include shanks and suitable reinforcement. This makes it much less likely that the garment will suffer damage from a button pulling free or the bother of having to find a match for a lost button.

Patching and darning are covered well, including how to pattern match the patch to the surrounding area.

Cutting down of garments is covered quite briefly here and it is pertinent to note that it is covered much more comprehensively in “Home Dressmaking” by the same author.

Fancy Dress commands a whole chapter and challenges the mother to look afresh at all manner of household items to see whether they could be utilized as costume. The author recommends a “Costume Trunk” into which can be thrown any old garments which would lend themselves well to being adapted to theatrical purpose as well as scarves, curtains, beads, woollen skeins and ribbons. Photos are given for a highwayman, a nun and an Arabian as well as instructions for making a wig out of wool and various ideas for curtains, pillowcases and old sheets.

Finally there are chapters dealing with baby equipment and nursery furnishing. Trimming a baby’s cot and providing the bedding is straightforward. More interesting to the modern reader is the idea of making the baby’s own mattress at home from a flour bag filled with chaff, this being – it is insisted – easy to wash and renew as well as being cheap to make and comfortable besides. Another cautionary word though: instructions are given for making an adorable wadded quilt, similar in looks to the satin eiderdowns so popular during the 1930s and 1940s. Modern childcare advice is to avoid the use of quilts on the bed of infants under the age of one; ours being an age of central heating the child would risk overheating and small babies can neither regulate their own body temperature nor kick off the excess layers. Instructions for making a larger one for an older child are also given and this would certainly be fine to make today as the size given (4ft long by 2ft 6 inches wide) clearly equates to a small single bed.

The final project suggested is a loose cover for a small armchair, one of which is often found in the nursery for the child’s use and I conclude that anyone who completed all the projects contained in this little book would clearly be very competent by the end of it!

Copyright of the blog owner 2013

09 Feb 2013 Leave a comment

in Book Reviews

A lovely little volume, hardbacked, measuring about 7″ x 5″ and with good quality, silky paper. It is a comprehensive volume, quite wordy compared to others of its type but the descriptions are clear and good and the diagrams, where they do appear are well drawn and easily understood.

I often measure the usefulness of a book by how well it covers the subject of gussets. I laugh whenever I write that but it’s true. I often make little garments with square-set sleeves which require a gusset set into the seam yet many books – thankfully not this one – deal only with the setting in of the triangular type commonly found as a reinforcement at the bottom end of a side seam on garments having a curved hem, such as a shirt with shirt tails.

It covers the absolute basics such as the correct way to use thimbles and needles, basic seams and hem stitches, casting on two and three knitting pins, darning, patching, the use of tapes and other reinforcements, buttonholes, turning a heel on a sock or stocking, working with pleats, tucks and gathers as well as decorative stitches.

The cutting out section happily contains workable patterns (illustrated upon grids and with dimensions clearly labelled) and useful hints about cutting out such as to caution against cutting a curved seam too deep as once cut out the curve cannot be made tighter whereas to cut away excess is comparatively simple.

Line drawings are also included of some of the finished articles, nicely drawn and with good attention to the detail and neatness which best tempts the reader to attempt the item. Shirts (both day shirts and nightshirts) for men and boys are covered here together with chemises, petticoats, night dresses, aprons, pinafores, combinations and drawers (knickerbockers) are all covered as are the techniques required for finishing them, for example the working and neatening of plackets, false hems (facings), sleeves, collars and bands. A wide selection too of infants’ garments together with example costings and suggestions as to suitable materials make this a useful resource for anyone interested in infantwear as with some obvious exceptions such as stomach bands much of these little garments are timeless.

It is also worth noting how unusual it is to have any boyswear covered in dressmaking books. As previously mentioned, boys shirts are covered here. I have often been disappointed to find that books purporting to cover the subject of childrenswear indeed concentrate purely on infantwear and beyond that, dresses for little girls; boys being seemingly forgotten. I’m not making the mistake of thinking that little boys didn’t wear dresses as toddlers either; one such book was published in the 1950s.

The third part of the book deals with the knitting or articles such as stockings and socks, knitted vests, petticoats and jackets, hoods, scarves and muffatees (a long, knitted cuff worn over the wrist and hand with a hole for the thumb), shawls and muffs, quilts, blankets and fringes. Netting, crochet, straw weaving and plaiting are also given a brief mention towards the end of the book.

In conclusion another very comprehensive but eminently usable book, well worth space on the bookshelf and not one I will be in a hurry to part with.

Copyright of the blog owner 2013

09 Feb 2013 Leave a comment

in Book Reviews

I am lucky enough to own the above books bound as a single volume but will review them separately.

Another highly rated little gem from my collection, this volume once again answers my desire to collect books which not only teach construction technique but which also give workable patterns, or instructions on how to create them so that perfectly authentic examples may be created without having to trust to the authenticity of patterns created for commercial sale by others.

The scope is obviously not particularly wide – you will not find herein the means to create a period ballgown or walking outfit but for the basic garments easily made at home such as childrens’ pinafores, chemises, overalls, aprons, knickerbockers, nightshirts and nightdresses for all ages, combinations, day-shirts and infants clothing you will find little better than this book.

The methods given are often simple – frequently worked to a proportional system of folding a sheet of paper – but this makes them very approachable. The garments are also made with the absolute minimum of waste – a Cottage Pinafore gives a very pleasing arrangement at the shoulder simply by clever cutting and with zero waste along that seam.

Written as an aid to teaching, this volume starts at the absolute basics. The correct use of a thimble, how to hold the needle, how to form a stitch – all are covered here. Knitting, darning and patching are also covered very comprehensively and ever with practicality in mind. As well as the ubiquitous instructions for hems, seams, buttonholes and decorative stitches here you will also learn how to turn the toe of a knitted sock, how to deal with a hem crossing a seam and how to sew the strengthening gusset at the foot of the side seam.

The discovery (or rediscovery) of methods still valid today but seldom taught are what make these old volumes such a delight. Anyone who has ever struggled to make gathers sit neatly would welcome the instructions for ‘stroking’ which induce them to lie in such uniform fashion.

The diagrams for cutting out are shown drawn against a grid, with dimensions clearly displayed for each piece, making it simple to recreate it for oneself. The grids are turquoise, the lines themselves either black or else red and they are very easy to interpret.

If I had to choose to keep only a fraction of my books, this one would surely survive the cull as it contains much that is covered elsewhere and more besides.

A companion volume to “Manual of Needlework and Cutting Out” by the same author and somewhat harder to come by, I am lucky enough to have secured my copy bound up with the former title as a single volume.

Whereas the earlier title also gave a substantial attention to cutting out and making up, it gave equal attention to the basic skills, seams, hems and techniques required in their making up. Such preliminaries are entirely skipped over in this second volume. I am happy about that as every other book I possess seems to demonstrate slip-stitching a hem and I would much rather dedicate shelf-space to new subjects.

A certain degree of overlap is admitted, especially in the clothing types for which the patterns and instructions are given but the patterns are not the same as those covered by the previous book and in addition to the chemises, petticoats, aprons and nightshirts, more advanced items are introduced such as some very fancy sleeves and sleeveheads and also techniques such as bone casings and gussets discussed in greater detail.

As the title suggests, this volume also gives detailed instructions as to the making up of the garment, the order and the types of seam suitable for each part. This makes it a valuable addition to the bookshelf of anyone interested in authentic techniques as well as the patterns of the turn of the last century.

Obviously a sewing machine could be used to save labour on the longer sections of the projects described in this book but it will be found that there are many areas, such as the insertion of square gussets, where hand-sewing is much simpler.

Copyright of the blog owner 2013

09 Feb 2013 2 Comments

in Book Reviews

This is a small, hard back book bound in red linen. Compared with the book “Dress Making” by Mme Trois Fontaines, published at a similar date the quality and size of the volume are inferior but despite this and the similarity in subject matter Ralston’s book still possesses plenty to recommend it.

The diagrams are not as large and clear as in the Fontaines book but the styles shown within are much more casual and practical. Where Fontaines supplies a great range of evening dresses, Ralston provides a sweeter and somehow more achievable selection such as a lovely, V-necked blouse, two different styles for a tennis dress and a number of dresses I would best describe as neat and stylish day-dresses for the modern, office-working girl.

Ralston does have one quirk which, as a trained pattern designer I have never encountered elsewhere – that of including a strange little tuck pleated into the shoulder edge of the bodice block exactly where one would expect a shoulder dart to appear. The block itself is drafted entirely without darts and this little tuck is intended presumably to supply the necessary ease for the bust.

Two foundation garments are provided as a basis for the patterns: a bodice and a sleeve. The skirt is drafted simply as a rectangle so not a block in the modern sense. The bodice block is incredibly simple, being dartless as previously mentioned and as with the other diagrams is simply a line drawing with red ink used for emphasising the main construction lines.

The drawings are less easy to follow than Fontaines, as the description of the type and colour of the lines used is described for the one and only time in Chapter V, before which point one simply had to muddle through with ones own interpretation. That said, the key is not a complicated one – red, solid lines to show the original block; red, dotted lines to show construction lines and black, solid lines to show the new pattern as it should be cut. This information appears before the pattern cutting proper commences so is not too far removed from where it is best needed although I do believe it would have been better to mention it before commencing the blocks as these make use of all three types of line but without the benefit of explanation.

Ralston is a more wordy volume than Fontaines but this is not to its detriment. Many a gem of advice is contained therein both on the subject of taking measurements correctly and in the proper manner in which to construct the garments, many of which tips are simply not widely covered today.

The style of reading is easy to follow and in reading it I was impressed that such a wealth of valuable information could be imparted so simply and so sensibly. There is nothing herein what Fontaines does not cover yet more comprehensively (and indeed liberally) but unlike Fontaines, the Ralston volume can be slipped easily into a pocket, a bookshelf or a handbag and covers wonderfully well a wide range of accessible and authentic patterns for anyone interested in this era.

Copyright of the blog owner 2013

09 Feb 2013 Leave a comment

in Book Reviews

Apart from the great beauty of the illustrations, wonderfully evocative of early 1930s glamour this book has two main strengths which particularly recommend it.

First is its size. The paper is silky and thick and at a hefty 14″ by 11″ it is quite a beast but this works to its advantage as the greater size of the diagrams makes them much clearer to follow and the notes with which they are labelled much easier to read.

Written instructions are concise, the diagrams being sufficiently clear and well labelled to act as the main source of instruction in recreating them.

The second area in which this book particularly succeeds is that of subject matter. Fundamental preliminaries such as accurate measuring and the adjustments to be made for various figure shapes/deviations are covered fully but succinctly, a mark of the both the confidence and the competence of the author, leaving the rest of the book for the patterns themselves.

It is rare in my experience to find a book so fully dedicated to the actual creation of patterns. Plenty of books relating to dressmaking flit quickly over the subject of pattern drafting. They may instruct how to make a basic block, a foundation garment from which to work but the majority then assume that you have purchased a pattern and need only to be taught how to set in the collar, work the seams, hems and buttonholes.

This book is quite the opposite. You won’t find how to make a bound buttonhole here. What you will find though is instructions for the basic foundation blocks, all worked to your own measurements, and a very generous number of style variations based on them, together with full instructions on achieving the same.

As I previously mentioned, the diagrams are large, well-drawn and clear. Refreshingly free of clutter, they are easy to follow and understand and are liberally used.

Anyone wishing to make up these styles exactly as they appear in the book would be advised to remember that the fashionable figure was long and slender, and the foundation bodice block uses a single long bust dart set into the shoulder seam – not at all appropriate for anyone with a full bust. However neither were the styles so if your figure is less than willowy you may have to forsake historical accuracy and draft a bodice better suited to your shape but the style ideas are here and may certainly be applied to a more modern foundation draft.

In conclusion this is a valuable resource for anybody interested in reproducing authentic 1930s clothing from equally authentic patterns. It would also make a wonderful addition to the coffee tables of anyone who loves beautiful books.

Copyright of the blog owner 2013

18 Jan 2013 Leave a comment

in Book Reviews

It made me smile to see how, over a century later, the same problems remain as tricky as ever! What follows is a transcription from the 1894 version of “Dainty Work for Pleasure and Profit” by Addie E Heron (including original typos and spellings) although the daily rate recommended her may need changing! That said though, consider that this amount was no mean consideration back in 1894 and is surely a reminder never to sell one’s time too cheaply:

and especially is this the case where parties are acquaintances, and may be friends. The social relation should not be considered in this connection, and the only successful method is to adopt a rule of procedure to be applied to all cases, and apply it impartially. Never accept an indefinite order, as

“my dear Mrs A. I believe I will have you get me up something for my dressing case, something pretty!” “What would you like?” “Oh, I’m not particular, just anything that would suit you!”

Never be betrayed into filling such an order. Insist upon the name of the article being specified, the nature of the work, the scheme of color, the amount of work, cost and nature of the materials, and last the price of the whole when completed. Make a memoranda of the items in the form of an order, read it to the lady and pass it to her for her signature. This will preclude the possibility of any mistakes being made, and leave no loophole for misunderstandings to occur when too late to rectify them. Be sure to fill all orders according to agreement, make out a bill for the work and present when the work is delivered, and insist gently upon payment at that time; if this is not possible have a definite time set when you are to call for the amount, and be punctually on hand. Women, as a rule are apt to be careless in regard to the payment of such bills, and allow them to run into indefinite time, but they will none the less be your customers because you insist upon your rights in a dignified manner.

When the parties are not known to you insist upon an advance payment of at least one half the price when the order is taken, and the balance upon delivery.

Do not work too cheap, neither be exhorbitant in your charges. Make the estimate of cost upon the time occupied in filling the order; at the rate of $1.50 per day is a fair consideration. When possible furnish the embroidery silks, linen or other threads used in your work; by this means you will always be certain of having correct shading and then, too, the profit on the same will be an item worth considering at the end of a year, as you will be able to make arrangements to secure these materials in small quantities of the wholesale houses.

The chapters on “Shading,” “Designing,” “Stitches,” “Materials,” “Art Embroidery,” including “Roman Embroidery,” “Kensington and Satin Embroidery,” “Application of Stitches,” and “Drawn Work,” contain all of the instructions necessary to thoroughly equip one for “Order Work”, without the aid of a teacher, if even the learner has had no previous instructions in embroidery, providing she has any natural aptitude for the work.

Copyright of the blog owner 2013

18 Jan 2013 Leave a comment

in Book Reviews